Vector of the composer's

AKSENOV FAMILY FOUNDATION PRESENTED THE SECOND SEASON OF THE RUSSIAN MUSIC 2.1 PROJECT

The concert of the laureates took place at the Moscow Philharmonic, which acted as a partner in this creative initiative. Four laureates created pieces for the symphony orchestra – musicians presented their works in the first part. Chamber music completed the concert program. The project attracted the attention of many music critics. We publish the opinions of three of them.

The strongest are coming.

Our composers have never given such a huge orchestra. One hundred and five people throughout the department played new works, even commissioned ones. For this, one could endure even a dubious appendage in the form of chamber performances. Project “Russian Music. 2.1” has reached a new frontier.

Adepts and practitioners of modern Russian academic music have often said we need a system of orders for new works. It cannot be replaced even by composer competitions, which have begun to flourish in recent years. And this is the second year since the launch of the Dmitry Aksenov Family Foundation program. In its format, composers receive orders, write music and then perform in public. The second year is important: many projects collapse in a year. And “Russian Music 2” began to gain momentum.

In 2020, composers were allowed to choose a lineup of five to eight people. It is the usual framework for the modern academic music, and Russian Music 2.0 only went up to them. But “Russian Music 2.1” in 2021 issued four symphonic orders. Again, the result exceeded expectations: four scores were better than one another.

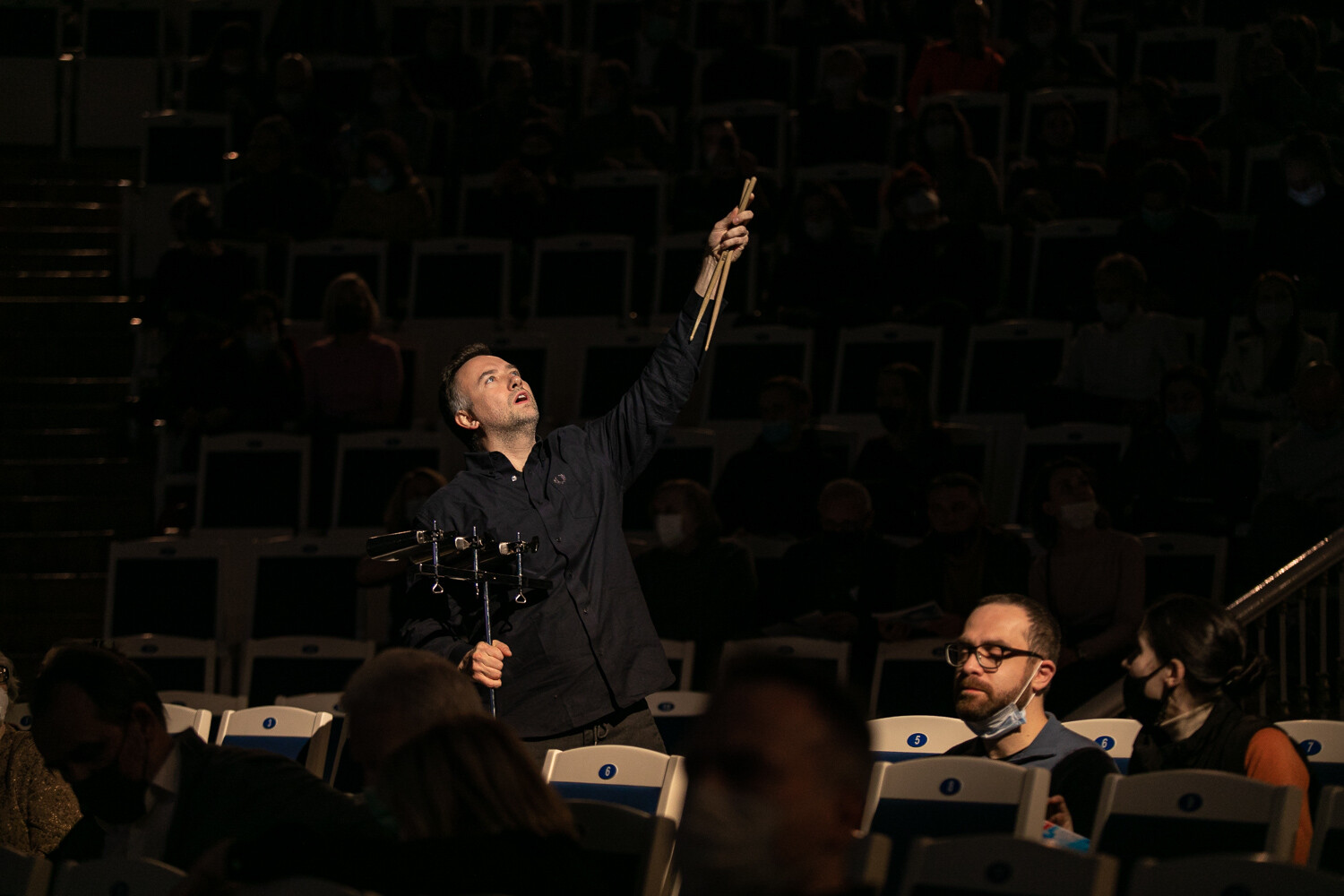

All four were performed in the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall, as the Moscow Philharmonic Society (as well as the Moscow Museum of Modern Art) acted as a project partner. The brainchild of the Philharmonic, the Russian National Youth Symphony Orchestra, turned out to be responsive to everything the authors came up with, and conductor Fyodor Lednev led the orchestra through all the trials with an experienced hand.

Composer Alexandra Filonenko, who lives in Berlin, used an orchestra in her Memory code opus with visual theatricality inherent in her style: a hundred types of drums sounded alone, but sound storms sometimes receded before the silence where wedged the sound of a phonogram.

Muscovite Oleg Krokhalev created the same full-length but very quiet and beautiful avant-garde composition, Catcher, in collaboration with sound engineer Felix Mykensky: the orchestra sounded from all sides – both from the stage and from the whimsically placed speakers.

The main instrument in the score of Vladimir Rannev from St. Petersburg’s “The Strongest” to the text of Thomas Bernhard (sung by Arina Zvereva, a skilled modern vocalist) turned out to be a triangle. Towards the end, the whole orchestra played on the triangles when the tension reached its limit.

Finally, in an opus by the Muscovite Vladimir Gorlinsky called “Terracotta” (the same Arina Zvereva and Olga Rossini soloed in it), part of the orchestra went on foot to the hall, from where it began to play open major chords, and the other part decided to sing.

Before each score’s performance, we saw more than serious interviews with composers on the screen: the common denominator of their positions was the cult of intuition and the superiority of the emotional world over the logical one. However, the scores proved the talent of each of the authors and their rational professionalism.

MCME musicians played four more pieces in the second part, also ordered as part of the program, but already chamber ones. The endless performance of Spokoyno by Alexander Chernyshkov was similar to all concerts and happenings, where the rehearsal process becomes the plot, spoiled by deliberate theatricality. Marina Poleukhina’s improvisation “A hovering heart stretches thepage until it floats” on kitchen utensils, combined with a drum and guitars, also recalled the board games of experimenters of the last century. The members of the Moscow Contemporary Music Ensemble, of course, showed the versatility of their talents in performing these tasks. However, they still listened organically to more academic chamber opuses, such as X is where I am by Elena Rykova or “How I spent this summer” by Anton Vasiliev.

However, the first symphonic department was the main result of the second year of the Aksenov Foundation’s work.

Peter Pospelov

Concert in terracotta colors

There were eight premieres by Russian composers at the Moscow Philharmonic. The concert of the laureates of the Russian Music 2.1 program lasted almost five hours and became a test of strength for both musicians and listeners. Unfortunately, not everyone survived – most of them watched the world premieres online (the Moscow Philharmonic carefully saved it on their YouTube channel in high resolution and with excellent sound quality).

Russian Music 2.1 is a support program for Russian composers from the Aksenov Family Foundation. Appearing a year ago, “Russian Music” (at that time 2.0) declared itself as a powerful tool for the composer’s order. There are no age restrictions here, but the laureates, selected by an international expert council, must present today’s music. In 2020, the program supported Alexander Khubeev, Alexei Sysoev, Boris Filanovsky, Mark Buloshnikov, Dmitry Burtsev, Oleg Gudachev, Daria Zvezdina, and Daniil Pilchen.

If in the 2020 season, the composers could choose the desired composition, this year it’s different: four worked with a large symphony orchestra, and four more wrote ensemble scores. Moreover, almost all the laureates of Russian Music 2.1 used electronics or video, extended compositions, or performance – they came up fully armed. And this is understandable: Aksenov Family Foundation not only paid a generous fee for a new piece but was also ready to fulfill any whim, whether it was seventy-five triangles for Vladimir Rannev’s score or crackers, wine glasses, knives, a bicycle tire, sandpaper and wet foam plastic for works by Alexandra Filonenko.

The concert was divided into two large sections: a symphony section with the Russian National Youth Symphony Orchestra (conducted by Fyodor Lednev) and an ensemble section for the expanded composition of the Moscow Contemporary Music Ensemble. In addition to instrumentalists, N’Caged soloists Arina Zvereva and Olga Rossini took part in the concert. A hierarchy has emerged (and this is distressing): a “serious” symphonic department, which is opposed by performative opuses with video art, light, and various objects. Moreover, the timing was discouraging: the first play of the second part lasted 55 minutes (!), compared to the rest of the 15-20-minute premieres. Wouldn’t it have been easier to separate two different and large-scale programs by making two concerts?

“Russian Music 2.1” curators announced the concert as “a playlist of contemporary music that will speak about its time.” Paradoxically, the “performative” part of the concerto looked highly archaic. Alexander Chernyshkov and his performance of Spokoyno and Marina Poleukhina’s score A hovering heart stretches the page until it floats. It is a homage to Cage, the Fluxus movement, and the musical avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s. Anton Vasiliev’s play “How I Spent This Summer” sounded like the experiments of James Tenney and Morton Feldman’s “lengthening,” spiced with microchromatic sound and a quote from Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto. The primary irritant in the play is the video sequence with animated notes (banality or post-irony?). The brightest and most exciting composition of the “performative” section is X is where I am by Elena Rykova. The composer shares his innermost secrets and delicately leads the listener along – as Yaroslav Timofeev, the host of the concert, rightly noted, “the piano became the heart of the score, and the singer’s voice became the soul” (soloist Olga Rossini, member of the N’Caged mezzo-soprano ensemble).

The symphonic part of the concert turned out to be the most solid and experimental. The play Catcher by Oleg Krokhalev, the youngest laureate of Russian Music 2.1, became a huge creative success. Subtle and musical, this piece absorbs the listener’s attention and live-electronics, which the musician and improviser Felix Mykensky led. That made it possible to consider the sound from different angles (I dare to hope that the Moscow Philharmonic Society will include this piece in the programs of the RNMSO). Vladimir Gorlinsky embodied the idea of “sound theater” on an even larger scale in the composition “Terracotta.” The program title is a ruse; the composition turned out to be a deep listening session. A colossal orchestra and two vocalists (soloists Arina Zvereva and Olga Rossini) moved around the hall, creating various acoustic situations and mesmerizing the listeners with sound magic.

Vladimir Rannev’s play “The Strongest” to the text by Thomas Bernhard was carefully thought out and built: from a compressed and tense impulse, as if an extract from the opera “Prose” (soloist Arina Zvereva), to a large-scale ringing culmination. But the memory code score by Alexandra Filonenko, which explores the memory phenomenon, needed more integrity. The massive and dense orchestral texture oversaturate with various kinds of micro quotations, modern playing techniques, and a vast number of sounding bodies (from knives and cups and saucers to pieces of wet foam). During the concert’s intermission, it turned out that during the performance, the sound department of the Moscow Philharmonic Society could not launch the audio over the orchestral sound. It means that the sound did not correspond to the author’s intention, and the actual premiere of Memory Code is still waiting in the wings.

The concert “Russian Music 2.1” raises the most critical question: what is Russian music today, and does it have borders? Of all the laureates, only two live in Russia (Vladimir Gorlinsky in Moscow and Vladimir Rannev in St. Petersburg). Alexandra Filonenko and Anton Vasiliev settled in Berlin. Alexander Chernyshkov and Marina Poleukhina in Vienna, Oleg Krokhalev studies composition in Düsseldorf, and Elena Rykova – Teaches in Boston. Russian composers abroad are not expat-losers (unfortunately, the senior colleagues sometimes express an opinion). They are in-demand personnel who write exciting and original contemporary music. It’s great that we heard their compositions in Moscow, thanks to the Aksenov Family Foundation. Now we were waiting for Russian Music 2.2 in 2022!

Vladimir Zhalnin

Aksyonov’s Ecosystem

The Russian Music program succeeded in what almost no one in the Russian community of new music could do: the creators managed to attract private sponsors – the Aksenov Family Foundation platform – and build a system of orders for composers. In addition, the organizers described the finalists’ concert as the year’s key event. In the booklet, they published almost a chronicle of the musical life of recent years. The project, of course, provides excellent support to composers, but does its positioning in the media match the result?

One gets the impression that Russian Music still needs a clear development plan. Last season, the organizers emphasized the need to establish ties with Western institutions and bring Russian composers to the world stage. This year, the opposite happened: Russian authors were presented to the Russian public because among the selected finalists, five of eight live abroad and have adapted well there but have yet to be known here. Last year, the creators were proud that they were bringing Music out of the professional ghetto and academic halls. Now, they are happy to cooperate with the Moscow Philharmonic and have the opportunity to play new compositions in the Tchaikovsky Hall.

Whether the Russian scene of new Music exists as something independent and original is a big question because Western composers are engaged in similar practices and explore the same formats as Russian authors. In international projects, artists from different countries often intersect and do not represent one state. In general, while trying to formulate the idea of “Russian Music,” there are difficulties.

The concert of the finalists of version 2.1 turned out to be large-scale in length (4.5 hours), and the performing forces involved in the participation. Organizers divide into two parts: in the first part, the compositions played by the Russian National Youth Symphony Orchestra, conductor Fyodor Lednev and soloists, and in the second part, the MASM in an expanded composition. The Moscow Philharmonic showed itself democratically, the leadership of which allowed all kinds of experiments to be carried out: the Tchaikovsky Hall became an independent instrument in this concert.

In the project “Russian Music 2.1”, the composers ordered several compositions for the orchestra. Alexandra Filonenko presented detailed work with instruments in her play Memory code. Her orchestra became almost an ensemble of soloists, and the composer wrote the parts in great detail and care. Unfortunately, there was a technical failure – the electronics did not work, so the performance can hardly be considered successful, but the musicians coped well with the problematic musical text. Only some things were possible to embody in the composition of Oleg Krokhalev. There needed to be more speakers in the hall, so creating a full-fledged panoramic sound was impossible. The piece Catcher used minimal orchestral means: few notes, each in its place. The composition uses the principle of converting the sounds of instruments into electronic ones, and bizarre bifurcations and stratifications of timbres arose in the hall.

In the composition of Vladimir Rannev “The Strongest,” we recognized the author’s style of the composer. The author realizes it in the texture, ways of interaction of voice and instruments, and text organization. Unfortunately, there was also a technical problem when performing at the concert. Due to issues with the microphone, Arina Zvereva’s vocals were drowned out by the orchestra ( the voice level was well in the broadcast). On the other hand, the youth orchestra musicians clearly liked the piece: in the second half of the work, they enthusiastically changed their usual instruments to triangles (there were 75 of them in the score). Vladimir Rannev solved the form of the composition interestingly: in the performance of the piece, the orchestra gradually transformed into one percussion instrument.

The exquisite work of Vladimir Gorlinsky, “Terracotta,” completed the concert’s first part. It is a mysterious, almost mystical spirit reminiscent of Messiaen’s “Turangalila.” If a combination of Martenot waves and classical instruments had a hypnotic effect in the symphony, then Gorlinsky’s immersion in a trance turned out without anything supernatural – only an orchestra and two solo voices (Arina Zvereva and Olga Rossini). Space played an important role here: in the middle of the play, some musicians settled down throughout the amphitheater and stalls, and the audience found itself in the ring of sound. The composer used a similar principle in his other piece, Bramputapsele #1, for drums, where the performer gradually seized the territory, moved along the hall’s perimeter from one instrument to another, and in the end, all the listeners found themselves in a single sound field.

The concert’s second part began during the intermission because the piece Spokoyno by Alexander Chernyshkov was composed as a rehearsal. It explored the process of creating music. The soloists of the MASM long and diligently depicted the preparation for the performance: they moved instruments back and forth, played something, moved furniture, talked to each other, and sang. Unfortunately, the Tchaikovsky Hall was unsuitable for this play because listeners could have read some of the plot lines and details better in such an ample space.

The composition, as a rehearsal, dragged on for almost an hour and destroyed the structure of the entire concerto. Nevertheless, it is a plus: the first part was too traditional and academic, so it was necessary to devise a way out of such a common situation. But, of course, there is another side to the issue. Most of the audience left during or immediately after the end of Spokoyno and have yet to hear the three remaining compositions.

After Chernyshkov’s theatrical play, Anton Vasiliev’s essay “How I Spent This Summer” was perceived with particular contrast. There was something almost meditative about it, like the view of the river in Cherepovets, which was broadcast on the screen. Another state, but also of a mystical quality, was conveyed in work X is where I am by Elena Rykova; singer Olga Rossini walked around the hall like a ghost, and the ensemble conjured something mysterious on the stage.

The evening ended with Marina Poleukhina’s play A hovering heart stretches the page until it floats, in which the auditory and visual intertwined into a complex but touching and sensual composition: recorded and live videos alternated on the screen, the musicians extracted sounds from the most unexpected objects.

The Russian Music project emphasizes the importance of creating an environment, but the question arises why only composers are supported. Young Russian performers who specialize in the contemporary repertoire are also in a plight because there are no grants, residencies, scholarships, or competitions; there needs to be more research and book publishing funding. Then what is an ecosystem? Orders for composers, of course, are necessary, but in this case, the problem of how new compositions can get, for example, into the programs of the world’s leading festivals still needs to be solved. For the music scene’s development in Russia, joint orders with foreign institutions are needed as co-productions of various opera houses in the musical theater. Russian music may have a great future if the project can co-finance the performance of world premieres in international institutions, thus organizing not a one-way movement to the West but a full-fledged creative interaction.

Irina Sevastyanova